Transportation

Introducton Data as of 9/26/2023

The following summarizes public school transportation in Loudoun County from 1870 – 1968. Public school transportation is part of the total picture of Loudoun County's public school evolution through this period. It is based on historical records found in the abandoned school house and other reference material. It also draws from interviews of former Loudoun County Public School (LCPS) students and bus drivers.

After Virginia established a state wide school system in 1870, (to include LCPS) education and the requisite school houses became more prevalent throughout the state. For almost a century it was a segregated system that kept Black and White students in separate school houses. For the most part Black teachers taught Black children and White teachers taught White children (with a few exceptions such as Quaker schools). Twenty-six years later (1896) the Supreme Court ruled that racial segregation was legal under a separate but equal doctrine. The education system was separate, equal it was not. Until LCPS began providing public school transportation, the predominant method used by Loudoun’s Black and White students was the same, they walked. The trip was usually no more than 3 miles one way. In that respect, school transportation between Blacks and Whites was equal, everyone walked to and from their neighborhood school.

By the early 1900’s the economy of scale emerged; consolidation of smaller schools into larger schools began. Led by then Superintendent W. G. Edmundson (1909-1917), smaller white schools in remote areas were consolidated into larger ones. However, with neighborhood schools closing, some students had to travel farther to get to school. To address this, public school transportation of white students began. Initially this took the form of horse drawn wagons of the nature of "school hacks" (see Table 1). The first of these is recorded in 1911 in the Jefferson district and was used to transport White students to the Hillsboro school (from the closed Salem and Edge Grove schools).[1] See Figure 1.[2] When there was snow, the wagon wheels were replaced with skis.

The first time a school bus was driven by a Black Man (Will Brown) was in 1937. Brown is also shown in the fiftieth Douglass High School anniversary book as one of those providing transportation in a station wagon he purchased. Dirt Don't Burn, pg 138. Footnote 37.

|

Date |

Description |

Manufacturer |

|

1827 |

First school omnibus (bus). Horse drawn wagon carried up to 25 students. Used to transport Quaker children to school in Abney Park (Stoke, Newington, London, U. K.) |

George Shillibeer |

|

1886 |

Horse drawn school carriages called "school hacks" |

Wayne Works (founded in 1837, predecessor of Wayne Corp.) |

|

1914 |

Mounted a school hack onto an automobile chassis |

Wayne Works |

|

1927 |

All steel bus bodies on automobile chassis |

Blue Bird Body Company and Wayne Works |

|

1932 |

All steel bus bodies on automobile chassis |

Gillig Bros. |

|

1939 |

School buses adopt the familiar yellow color with black lettering |

Dr. Frank W. Cyr (organized conference establishing school bus standards) |

|

1930's - 1950's |

Type D bus (flat front end design also called transit-style) |

Wayne Works, Crown Coach, Gillig Bros. |

|

1950 |

Transit-style design (Type D) evolves into the Blue Bird All-American (first successful east coast school bus transit design, though Type C with conventional truck type hood and front end dominates US school bus manufacturing through end of the 20th century) |

Blue Bird Body Company |

|

1959 |

First rear engine, diesel powered school bus is introduced. The C-180 transit Coach becomes most popular rear engine transit-style school bus on the west coast. |

Gillig Bros. |

Table 1: Summary of the history of school bus evolution[3](Boveri 2013)

See: Hillsboro School [Photo], 53-0237 Lewis/Edwards Architectural Surveys of Loudoun County 1972 – 1983(M 022), Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg, VA

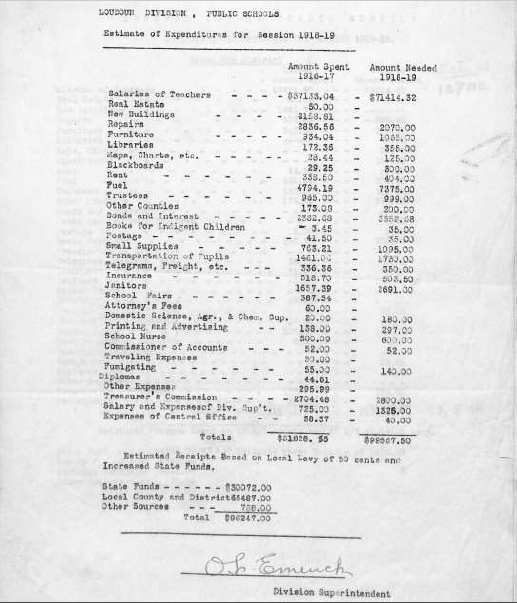

Superintendent O. L. Emerick (1917 -1957) continued the consolidation of smaller White schools into larger ones and the county’s public school transportation system grew. Records indicate LCPS had a 'Transportation of Pupils' expenditure of $1461.00 for the 1916-1917 school year (see Figure 3[5]). This is very likely the cost of transportation using "school hacks". LCPS moved from "school hacks" to gas powered school buses between 1924 and 1925. Still, these buses served only white students at first[6]. Given the Jim Crow environment, and records found by the Edwin Washington Society, it is unlikely that Black students were transported to school using county provided transportation before 1937.

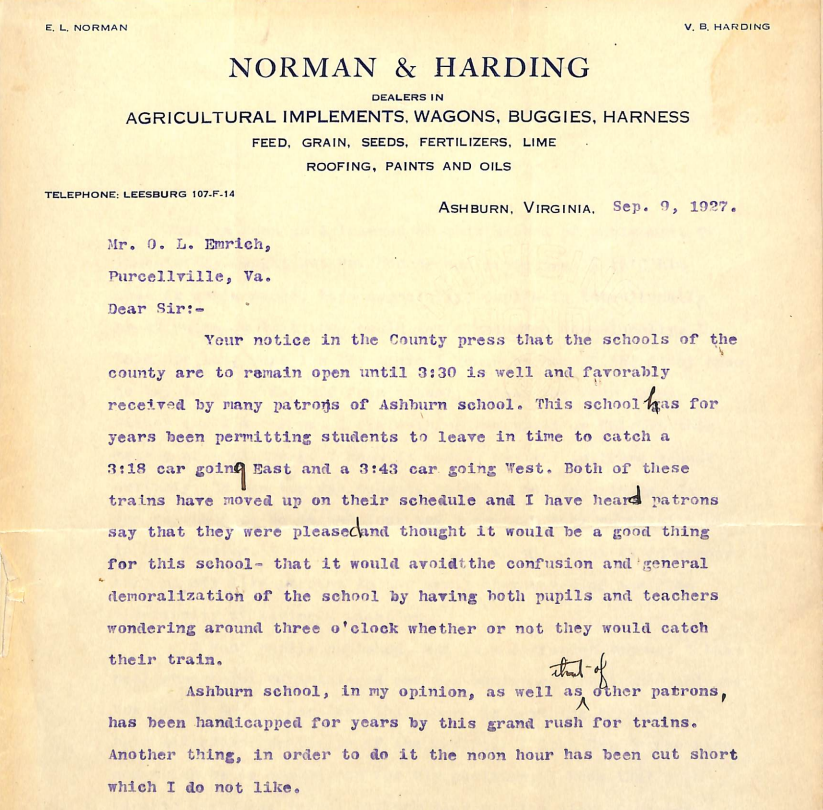

From the beginning, Black and White parents and patrons petitioned the school board for various changes. Records of these written petitions were part of the cache of records found in the abandoned school house and reviewed by volunteers of the Edwin Washington Society. Transportation issues accounted for 18% of all "colored" petitions and 13% of all White petitions that Edwin Washington volunteers reviewed. By the 1920’s students walked, were bussed and even used the Washington and Old Dominion (W&OD) railway line. This indicated by a 1927 correspondence from Victor Harding whose topics included students leaving school early to catch the train[1](see Figure 4). It appears students' lunch hour was cut short to accommodate early departure.

Overcrowding was one driving force for the need for public school transportation. As students graduated from elementary schools, they usually needed transportation to get to the nearest high school. Lacking transportation to a high school, the students continued to attend their old elementary school. This resulted in overcrowding and could also be a source of disruptive behavior. White parents of students of the Brooklyn school in the Lovettsville district, highlight overcrowding and the need for transportation in their 1931 petition. A final topic of this petition stated:

"That quite a number of the pupils in said school have long since passed the required examinations for admission into High School but because of the distance and in-accessibility (sic) of a High School continue to go to the said Brooklyn School which condition is conducive to the condition above complained of in paragraphs # 1 & 2,[2]"

Note: paragraphs # 1 & 2 dealt with issues from overcrowding.

Another driving force for the need for transportation was the lack of a minimum number of students (the other end of the student population spectrum). Some schools had to close because they had too few students. Those students left would loose their neighborhood school and may now be farther away from the next closest school. In October of 1934 patrons of the Bluemont Colored School addressed the condition of school closings with the following petition.

In view of this condition, we the patrons of the Bluemont Colored School, are asking the Loudoun County Board of Education to give us transportation for seven pupils, to Rock Hill School with the teacher; as she passes through Bluemont going from Purcellville to Rock Hill School.

We the undersigned persons believe that this request is reasonable. [3]

The Bluemont school closed in 1932/33, and yet by 1934, LCPS still had not provided transportation for Bluemont students. Their patrons and parents had to petition for consideration. The earliest record of a school bus delivering students to Rock Hill is 1936/37 (see Figure Y). [4]

Transportation issues raised to LCPS, included road conditions as shown in a 1932 letter from patrons and parents of Black students attending the St. Louis school.

Middleburg, Virginia

January 21, 1932

Mr. O. L. Emerick

Purcellville, Virginia

Dear Sir:

We, the patrons of St. Louis School, are very anxious to have the roads entering the school grounds improved It is in a terrible condition, making travel upon it almost impossible. If possible, we should like very much to get help from the School Board. We are willing to contribute labor towards the work. Sincerely yours, James S. Grant, Robert T McQuary, Dudley Gaskins, Sam Hamblin, Myrtle McQuary, Clarence Howard, Mollie Evans, Laura Cook, Teacher [5]

It is important to note that this letter was written before LCPS provided buses for Black students. These patrons were concerned about damage to their private vehicles and offered their own labor to repair the road leading to the school. Records show that the Black patrons and parents of Loudoun didn’t sit idly by waiting for LCPS to provide school buses. In addition to petitioning LCPS, they used their own private vehicles to transport students to schools (reference interviews and excerpt from the Douglass High School 50th Anniversary publication in the following pages).

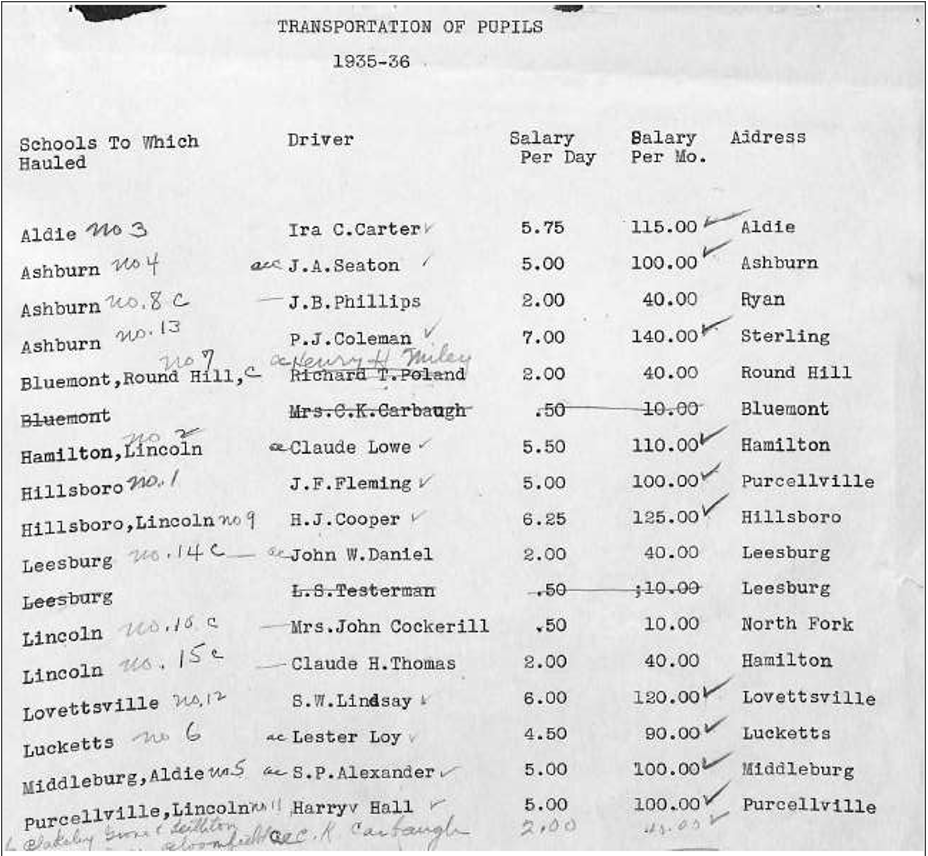

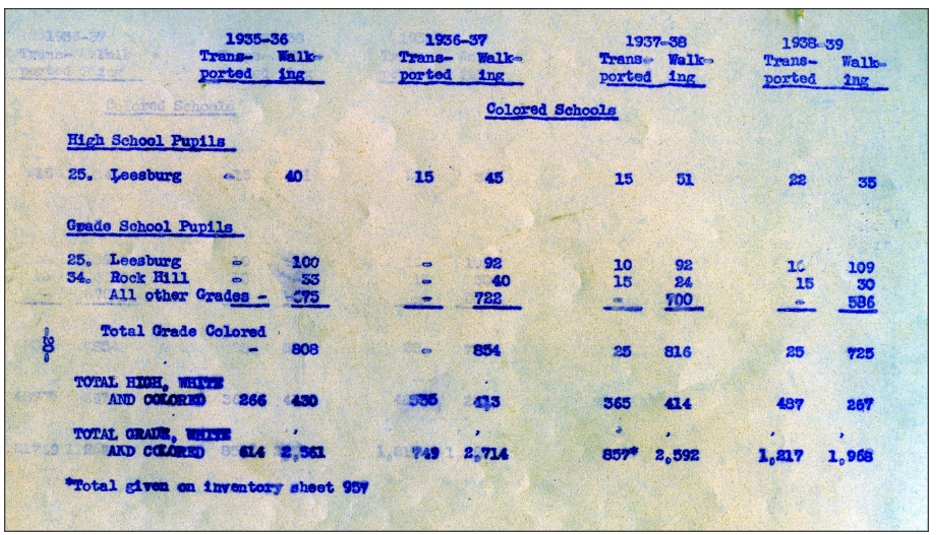

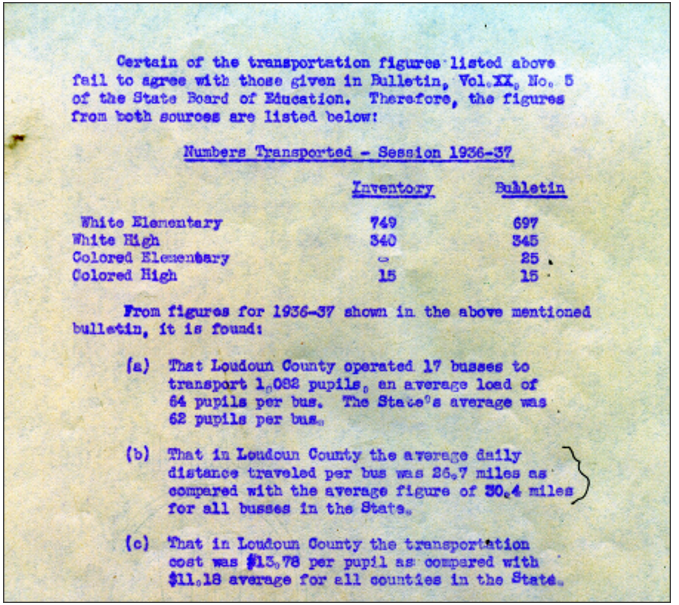

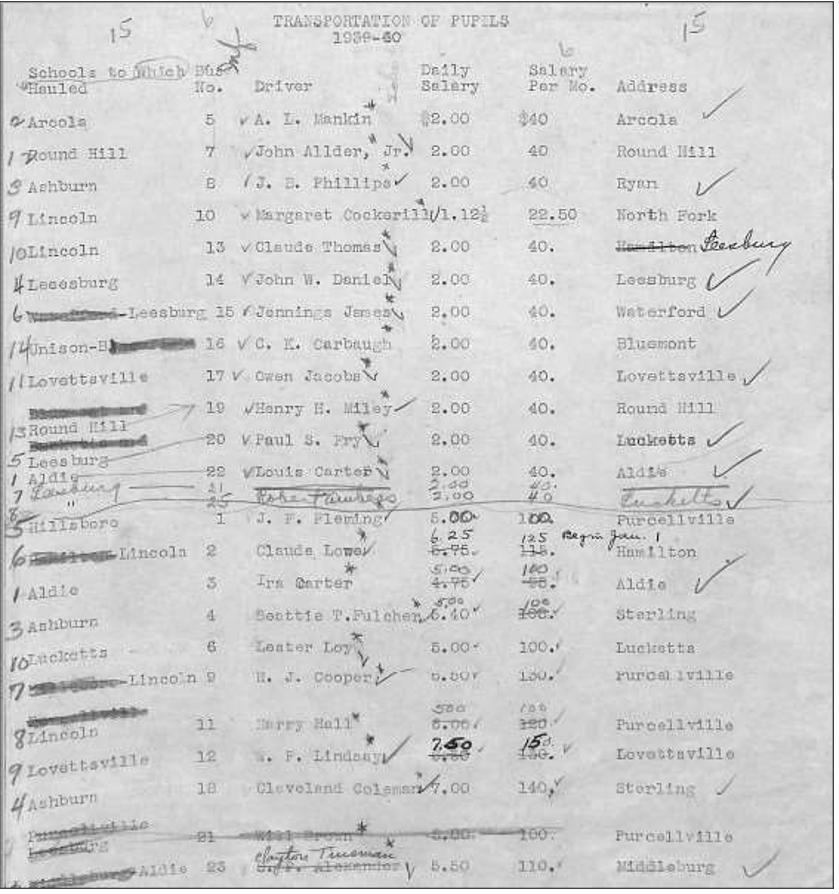

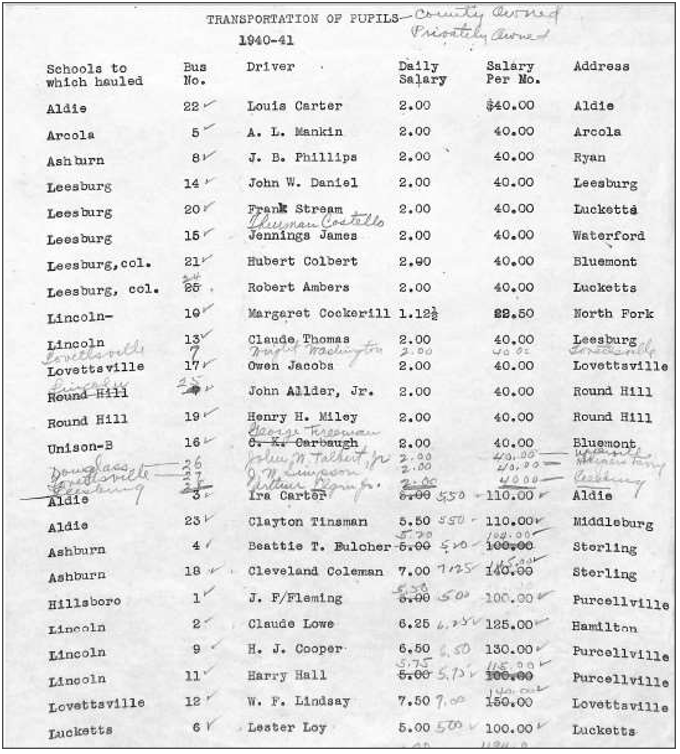

A roster of 1935-1936 bus drivers and their respective 16 routes is shown in Figure 4.[6] Research finds all these drivers were White. There were no Black bus drivers employed by LCPS transporting Black students at this time. Figures 5 and X paint the following picture: no Black students transported by LCPS before 1937; LCPS transportation costs of $800 for Black students in 1937; the reference to ‘Brown’ was very likely Will Brown, first recorded Black driver employed by LCPS. Brown’s route ran from Purcellville, through Hamilton and Waterford to the Leesburg School (Leesburg Training Center)[7]. In 1937, twelve years after school buses are introduced in Loudoun County the first LCPS school bus for Black students is placed into service. Figure Y further corroborates this stating that there were 17 bus routes in 1936/37 (assumed 16 White and 1 Black).[8]

[1] From EWP 2.5B Yr. Sept 9, 1927... permitted& to leave school early in order to catch the 3:18 train going east and the 3:43 going west.

[2] EWP 2.5B Yr. February, 1931 An exchange of correspondence between the patrons and friends of Brooklyn and O.L. Emerick.

[3] EWP 2.5.A Yr 1934 Oct 3 Bluemont Needs Transport to Rock Hill.

[4] EWP 9.3 Yr 1940 Construction and Pop Study, pg 21

[5] EWP 2.5.A Yr 1932 Jan 21 St. Louis Road Needs Improvement.

[6] EWP 12.2 Yr 1935 to 54 Bus Drivers (1935-36)

[7] From Timeline of Important Events in African American History in Loudoun County, Virginia by Gene Scheel; From website: http://www.loudounhistory.org/history/african-american-chronology/ Accessed Sep. 29, 2020

[8] EWP 9.3 Yr 1940 Construction and Pop Study, pg 21.

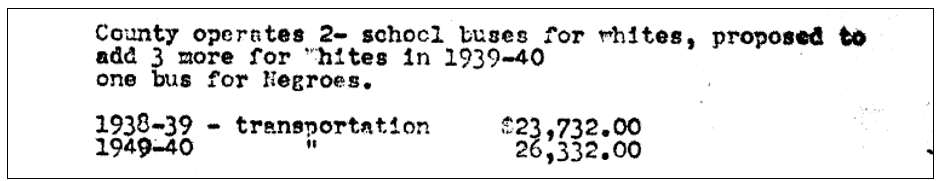

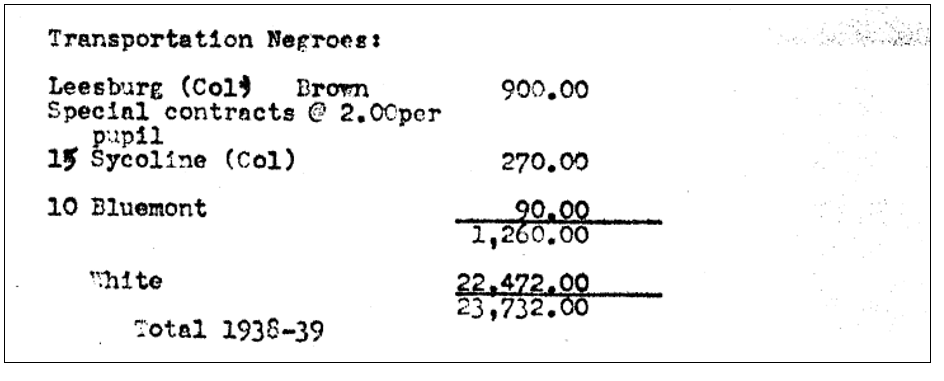

Transportation disparities between Black and White students in the 1930's are revealed in Figures 5 and 6. These figures are excerpts from National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) papers for Loudoun County. The county spent $1,260 for Black transportation and $22,472 for white transportation in 1938-39. [1].

LCPS operated 20 school buses for academic year 1938/39, but only owned ten. The remaining 10 were owned by private contractors. Of the twenty, only one was used for African-Americans, which we presume was Leesburg. It was proposed to add three buses for white student in 1939/40; but no provision was offered for African-Americans.[2] It would be the 1940-1941 school year before an additional two buses were made available for Black students (see Figure 10).

Throughout this period, the roads were a combination of dirt, gravel and asphalt with roads in the farther reaches of the county being dirt and gravel. As noted by Gertrude Alexander (Jeanes Supervisor for “Colored” Teachers) in her 1940 paper:

“Most of [the schools for African Americans] are located in small communities away from the main highways [on unpaved roads], which makes transportation in the winter months quite difficult."

She also noted in her paper that:

“many of the schools are located so far from the population centers that children are compelled to walk many miles to school.” [1]

This presented problems in muddy weather for outlying communities (Black and White). There are accounts of school buses mired so deeply in mud that farm tractors were used to pull them free.

"We were picked up and transported by bus to the school. All roads were still dirt with maybe a little gravel in places. In wet weather or snow, ruts would develop and they became almost unusable, it was a very common thing to get stuck. There still at this time was very little traffic."[2]

Furthermore, when it snowed the dirt and gravel roads were the last ones plowed (if at all).

The late 1930’s saw the student bus driver emerge. High school students (generally Junior and Senior boys) with a valid driver’s license, that had passed a special driving test were paid to drive students to and from school. In the morning they’d deliver students to school, park the bus and then attend their high school classes. In the afternoon, these drivers would leave early in time to pick up students when schools let out and take them home. There were both Black and White student bus drivers and, based on interviews this practice continued at least through the 1960’s (see interviews and bus driver rosters).

In 1940 there were 22 White bus routes and 1 Black bus route (see Fig 9).[3] In March, 1940, patrons of the Willisville Colored School wrote letters stating that because of lack of transport, children arrived at class wet and cold, missed school for two or three months, further that the smallest ones "cannot get to school at all." and return to home in near dark, in some cases having to walk three miles each way. The same letter spoke of children being run off the road and no provision to transport students to the Training center for high school. As one of the Willisville letters put it, "we certainly do need a bus for our children an above all a high school for we have many boys and girls ready for high school to be turned out in the world to go to destruction when they can be in school."[4]

While most transportation concerns were addressed by petitions with multiple signatures, individual patrons also wrote to express their needs and concerns. In order to put pressure on the school board to provide for her daughter's transportation to Leesburg (12 miles), Ms. Annie Wyatt, (a Black widow) of Sterling, Virginia, sent a creative letter in 1940 with an itemized bill for her 16 year old daughter’s school transportation. It read in part as follows:

"I am sending in my bill for the transportation of my daughter Ruth Elizabeth Williams to the Loudoun (sic) High school, for the year, 38-39 and the year 39-40. She is transported by the Washington-and Old Dominion railway. The fare per month is $6.70." [5]

Attorney Charles H. Houston (NAACP) was enjoined to take up the transportation issue Black parents had with LCPS[6]. An example of a plea for Mr. Huston's help came from Mrs. Mary Page of Upperville to attorney Charles Houston on March 8, 1940.

"I have a girl who is ready for high school this fall and there is no means of transportation made yet. I do hope that you will work in our behalf in helping to provide ways for them to get in high school."[7]

It's approximately 26 miles between Upperville and Leesburg, VA.

In March 1940 Mrs. Elizabeth Warner of Bluemont, VA. also requested the support of Attorney Houston, hoping to address a transportation issue with her letter:

"...I am one of the Willisville patrons and am much concerned about transporting the children to high school. I have two that have finished the elementary school two years now and are still out of high school. I am poor and have no way of getting them to Leesburg. W (sic) I trust that you will help us all you can to put this deal over." [8]

It's approximately 24 miles between Willisville and Leesburg, VA.

At the same time, Black parents sought an accredited Black high school (the Leesburg Training Center was woefully inadequate and unsafe). The efforts of Black, Loudoun County patrons, parents, the County Wide League, the Parent-Teachers Association and attorneys like Charles Houston paid off. In 1941 Douglass High School opened (with limited bus transportation). It would remain the only accredited Black high school in Loudoun County for over 2 decades. It follows that school buses were the obvious solution to transport Black students from the far reaches of Loudoun County to the only accredited Black High School.

Black adults used private transportation to transport Black students to Douglass before their areas were served by school buses. As stated in the 'Douglass High School 50th Anniversary 1941 1991' publication:

"Mr. William Brown of Purcellville provided transportation for the students in his area and also Hamilton. Mr. Towney Ferrell, SR. and Mr. Arthur Jackson of Waterford, Mr. C. P. Cook, SR of Middleburg and Mr. Rob Ambers of Lucketts in their areas. In the later years, Mr. Brown purchased a station wagon. Students from Waterford were picked up in Paeonian Springs. If their ride failed to show, they would board the train for a ride to Leesburg school. Louise Ferrell of Waterford was always anxious to go to school, and would hitch-hike if her ride did not come."

The train referenced above would have been the W&OD rail line. Mr. Rob Ambers (Aubers) of Lucketts is very likely the same person shown as a bus driver in Figures 9 & 10. Furthermore, the publication goes onto state:

"Students from Ashburn and surrounding areas were transported by train and those outside the town limits of Leesburg either walked or came by horse and buggy."

"Parents donated money for gas to those who provided transportation for their children."

Further indication that the Black patrons and parents of Loudoun County were determined to see that their children received an education. They bore the cost of private transportation when the county failed them. The publication's dedication page states:

"We dedicate this book to the Parents, County Wide League, NAACP and other supporters for their unswerving devotion to higher education of the youth in Loudoun County." [9]

[1] Special Report of Jeanes Teacher for School Year 1939-1940 for Loudoun County, Robert W. Woodruff Library of the Atlanta University Center.

[2] From Growing Up Lovettsville The Life and Times of Water M. Fleming pg 22; Walter Fleming started being bused to Lovettsville elementary after Woodland/George's Mill closed in 1937/1938.

[3] EWP 12.2 Yr 1935 to 54 Bus Drivers (1939-40)

[4] Letter from Patrons of Willisville School to Charles H. Houston, March 1940. Personal Papers of

Charles Houston, Founder Library, Howard University.

[5] EWP 1.1.1 Equal Education re Transportation: 3/31/40. Letter to Emerick from parent Annie Wyatt requesting reimbursement for Transportation costs. Note: Ruth Elizabeth Williams would have been required to sit in the rear of the railway car.

[6] Paul Young of Bluemont had a child who needed to walk 3.5 miles to the Willisville School, so he pled with Charles Houston to ask the school board for a bus. Letter from Paul Young to Charles Houston, March 10, 1940. Archives of George Mason University.

[7] Letter from Mary Page to Charles Houston, March 8, 1940. Archives of George Mason University.

[8] EWP NAACP papers_Loudoun_pgs_1_to_50 (1) pg 10

[9] From: Douglass High School 50th Anniversary 1941 1991

African American parents in Middleburg used their resources to hire Alexandria, Virginia, attorney James H. Raby to confront the dual issues of overcrowding at Grant School and transportation. In his November 1944 letter to Oscar Emerick, Mr. Raby addresses these issues in the contexts of Plessy vs. Ferguson and blatant racism. In addressing the plight of black children who had no transportation to school, Mr. Raby states in his letter that

"...out of the twenty four children that do not have the transportation, many of them do not attend school and their excuse is that they get tired of walking. Now with all fairness to the school board I do not think this hardship should be placed upon the children."

He goes on to say that

"I am mindful of your last letter in which you stated that the bus carrying white children and passed these children going to school, you had requested the driver to pick up these children but he had refused to do so. The only way I see to remedy this condition is to supply these children with a bus just the same as the white children, who have a bus."

Mr. Raby's letter confronts the superintendent with the separate but "equal" doctrine that had then been in place for five decades after Plessy as follows:

"...my only concern is that the school board make sufficient provisions for these children in as much as we do have the dual system of the school. It is the duty of the school board to provide equal facilities for the school children and it is the school board's duty to provide equal transportation."

Finally, he addresses overcrowding in Middleburg:

"You have received a letter from a number of the parents in Middleburg complaining of the crowded condition at Grant school. ... there were two rooms of which ninty-six (sic) students had to be cared for by two teachers. Under these conditions, there is no way these children can get adequate training. ...there is not any reason for such condition because there is ample space to enlarge the school building." [1]

School consolidation continued. One and two room schools were closed and larger schools opened, and now it began to affect Black schools (nearly thirty years after school consolidation began for Whites). The consolidation resulted in more pressure from Black parents for transportation. Petitions from Black parents continued to urge LCPS to provide services for their children. In 1948 Banneker and Carver opened, consolidating smaller Black schools like St Louis, Willisville and Hillsboro Colored school. Bus driver rosters from the 1940’s and 1950’s show a steady increase in the number of buses for Black students.

According to bus inventory records, county owned buses for Blacks and Whites were generally driven for no more than 10 or 11 years after which time they were replaced with new ones. Old buses were sometimes used as spares or even sold to the public. Available records show that by the late 1940's, salaries paid to adult, LCPS Black and White drivers were pretty much equal (see Table 2). Salaries for student bus drivers were usually half that of the adults.

|

Yr |

1946/47 |

1947/48 |

1948/49 |

1949/50 |

1950/51 |

1951/52 |

1952/53 |

1953/54 |

1954/55 |

1955/56 |

|

Black |

$55/mo. |

$60/mo. |

$80/mo. |

$80/mo. |

$80/mo. |

$85/mo. |

$90/mo. |

$90/mo |

$90/mo |

$90/mo |

|

White |

$55/mo |

$60/mo. |

$80/mo. |

$80/mo. |

$80/mo. |

$85/mo. |

$90/mo. |

$90/mo |

$90/mo |

$90/mo |

Table 2: Salaries of Black and White School Bus drivers (LCPS employees)[2]

Private contractors, (those that owned their own bus) were paid between $140 - $280 per month for this same period[3].

From 1937 through the height of integration in 1968, the number of school buses serving Black students continues to rise.

Blacks received separate, county provided school transportation nearly twenty years after they were first used for white students. The records show an unequal distribution of buses for the Black community, (e.g. initially, a single bus serving the only Black High School in the entire county). The records also show that the introduction of buses for Black students was much slower than for white students. This meant that the general population of Black students traveled by foot, private vehicles, horse or wagon longer than their White counterparts.